Introduction

Autonomous AI agents are rapidly moving from experimental demos to real-world economic actors. As these agents evolve from mere assistants to independent decision-makers, stakeholders need new metrics to evaluate their effectiveness. Traditional ROI alone is not enough – we must gauge how much autonomy an AI can exercise per unit of capital spent. This is the essence of the Autonomy-to-Spend Ratio (ASR). In simple terms, ASR measures “the most value possible – the most juice – out of our AI tools for the least amount of … input, but instead of human effort it focuses on financial input. A higher ratio indicates a greater return on investment in intelligence – akin to a “purest measure of productivity amplification” for autonomous systems. This concept is especially relevant in AI-native economic systems, where autonomous agents manage budgets, transact value, and make investment decisions without constant human oversight.

Across venture capital, enterprise innovation groups, and AI strategy teams, the same question keeps coming up: can an autonomous agent justify its own economics? The issue became especially clear when evaluating AI-driven roles like an autonomous Site Reliability Engineer. Traditional software tends to have mostly fixed costs, but advanced AI agents operate differently: they incur expenses with every inference, every reasoning step, and every API call. Each cognitive operation—processing tokens, running tools, or executing multi-step chains—directly contributes to real, measurable cost.

In AI-driven markets (e.g. blockchain-based systems), agents even hold their own wallets and pay for resources autonomously. ASR emerges as a key metric to quantify how effectively an agent converts those expenditures into autonomous productive work or value. By analyzing ASR, stakeholders can ensure AI agents deliver real-world value, not just flashy capabilities. The remainder of this paper defines ASR and maps it to investment criteria, surveys current and future use cases, and proposes a quantitative framework (including telemetry and threshold bands) for this metric.

Defining Autonomy-to-Spend Ratio (ASR)

ASR is defined as the ratio of an agent’s autonomous output or value generated to the resources (spending) it consumes. In formula terms, one can think of:

This encapsulates how self-sufficient and cost-effective an AI agent is. A higher ASR means the agent accomplishes more tasks, decisions, or returns per unit of budget, indicating efficient use of capital with minimal human intervention. For example, if an autonomous trading agent is given \$1M and it independently generates \$200k profit, its ASR (in terms of ROI) might be considered 0.2 (20% ROI achieved autonomously). But ASR also captures more than profit – it gauges the fraction of decisions and actions taken without human input relative to the spending. An agent with ASR of 0.8 could be interpreted as autonomously executing ~80% of its allocated financial decisions (and likely yielding proportional returns) without external guidance, whereas an ASR of 0.1 implies it’s mostly waiting on instructions despite using some budget.

Crucially, ASR links to the leverage of autonomy. It asks: for each dollar (or token) spent by the agent, how much “intelligent work” is done independently? This aligns with recent views on measuring AI by output vs input. For instance, Jarad DeLorenzo’s Agent Autonomy Ratio (AAR) tracks how many minutes of unattended work an AI yields per minute of human prep time. ASR simply shifts the focus to financial input: How many units of value or task completion do we get per unit of capital expended? In AI-native economies – systems where agents trade, invest, and operate with digital tokens or budgets – ASR becomes a vital health metric. It reflects an agent’s economic autonomy, which blockchains and smart contracts now enable by giving AI direct wallet access and the ability to transact without a human in the loop. A high ASR indicates an agent truly functions as an autonomous economic actor, not just an automated tool. In summary, ASR measures the “intelligence yield” on spending – a bridge between technical capability and economic efficiency in autonomous systems.

ASR as an Investment Evaluation Metric

Why does ASR matter to investors and strategists? In traditional ventures, investors look at burn rate versus traction; in AI ventures, ASR plays a similar role by quantifying how effectively an AI-driven system uses capital to generate results. Below we map ASR to evaluation criteria for various stakeholders:

- Venture Capital & Investors: For those funding AI startups or agent-powered platforms, ASR is a KPI indicating capital efficiency. A startup deploying a swarm of autonomous agents with an ASR of 0.7 is essentially getting 70% of its spending converted into productive autonomous work – an enticing prospect. High ASR suggests an AI product can scale revenue without proportional human costs, improving margins. Investors will compare ASR across companies: much like LTV:CAC (lifetime value to customer acquisition cost) is used for SaaS, Value:Spend for autonomous agents could predict which agent networks sustainably amplify capital. If one trading agent network consistently achieves higher autonomous ROI per token spent than another, it signals a better bet. Conversely, a low ASR warns that most spending is wasted or requires human babysitting, undermining the “AI” value proposition. As a simple illustration, Fuzzy Labs found that their autonomous SRE agent only needed to solve 15% of incidents correctly to be cheaper than a human-only approach. This implies even an ASR of 0.15 can justify investment if the scale is large – a remarkably low bar that hints at how attractive moderate autonomy can be from an ROI perspective.

- AI Strategists & AI Investment Strategists: Enterprise AI leaders and corporate investment directors use ASR to decide where to deploy AI and how to budget for it. ASR aligns with concerns like cost savings, scalability, and risk. A strategist might set a target ASR (say 0.5) for an autonomous customer service agent initiative – meaning at least half of routine inquiries should be resolved per dollar of operating cost, with the rest possibly escalated. This blends technical success (accuracy, goal completion) with financial discipline. Operational metrics feed into ASR: automation rate, cost per interaction, time saved per task, etc., all roll up into the value side of the ratio. Strategists also use ASR to assess scalability – if adding more budget yields proportionally more autonomous output (maintaining or improving ASR), the system scales well. If ASR drops when scaling, it flags diminishing returns. Additionally, ASR provides a common language between technical teams and finance: it translates tool efficacy (which might be measured in accuracy or reward score) into business terms of output per spend, facilitating better governance and funding decisions.

- Agent Developers & AI Engineers: For those building the agents, ASR is a North Star metric guiding technical improvements. Developers are essentially tasked with increasing the numerator (autonomous value) and minimizing the denominator (cost). This is analogous to maximizing Jarad’s autonomy ratio (more unattended agent work, less human input), but here it’s about cost-efficiency. Engineers can break down ASR into components: model inference costs, API call expenses, success rates, and iterative loops. They will ask questions like: Can we fine-tune the model to require fewer costly calls? Use a cheaper local model when possible? Each breakthrough that “either increases the amount of time (or tasks) the agent can work unattended, or decreases the prep (or spend) required” boosts ASR. The timeline of autonomy improvements – from early ChatGPT yielding an autonomy ratio ~0.1, to modern agent frameworks hitting ratios above 10 in terms of output per input – shows developers constantly pushing this efficiency curve. ASR provides a quantifiable target for optimization (much like latency or accuracy targets): e.g. “reduce cost per query by 50% while maintaining output quality, to improve ASR from 0.3 to 0.6.”

- Tokenomics Designers & DAO Governors: In crypto networks or decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) involving AI agents, token economists can use ASR to design incentives. For example, an Intelligence DAO funding autonomous research agents might allocate more tokens to agents or modules with higher ASR, as they yield more autonomous research per token. Tokenomics mechanisms (staking, rewards, fee structures) can be tuned to favor efficient agents – effectively creating a market for autonomy. If an agent’s ASR is high, it could be rewarded with a larger budget from the DAO treasury since it’s likely to generate proportionally higher returns or outputs for the community. On the flip side, mechanisms like slashing or budget reduction can be applied to low-ASR agents that waste resources. Governance reports in such DAOs would likely include metrics like autonomous ROI (returns agents generated vs. funds allocated) and efficiency scores akin to ASR for each project or agent cluster. Ultimately, designing an economy around ASR means aligning the network’s token distribution with the principle of “autonomous agentic capital” – capital that largely deploys itself. As we discuss later, when ASR exceeds about 0.6, one can think of the capital itself as “self-directed”, a scenario token designers are actively trying to encourage in next-gen decentralized AI platforms.

Near-Term Use Cases Demonstrating ASR

Today’s AI agents already exhibit varying ASR levels across different domains. Here we highlight several near-term use cases, grounded in current capabilities, where autonomy-to-spend dynamics are especially visible:

- Autonomous Trading & Investment Bots: Perhaps the clearest early example of agents operating with financial autonomy, trading bots in stock and crypto markets execute thousands of decisions with minimal human input. Modern AI-powered trading bots can “make split-second decisions in volatile trading environments”, often outperforming human traders. Many crypto funds now run on algorithmic agents that manage portfolios end-to-end. The ASR for a well-tuned trading bot can be quite high – once it’s fed initial capital, every trade it makes (spend in the form of capital allocation and transaction fees) is an autonomous action toward profit. Reports indicate some AI bots achieve annual returns of 25–40% with very few manual interventions, implying a large portion of the investment decisions (and returns) are coming autonomously. In practice, a bot with a win rate of 60% and strict risk controls might, for every \$1 of trading fees and slippage (spend), generate several dollars of profit – an ASR well above 1 in pure ROI terms. Even more telling is how little oversight some of these run with: e.g. fully automated arbitrage bots operate 24/7, only alerting humans when certain risk thresholds are hit. Such systems approach the self-directed agentic capital regime, where the agent is essentially a fund manager. Notably, the first documented case of an AI agent turning a profit on-chain occurred with Truth Terminal, a bot on X (Twitter) that was given a crypto wallet. After receiving a deposit of a memecoin, it autonomously promoted the token on social media, causing its value to spike ~9× and making the agent a “crypto millionaire”. This real-world anecdote underscores how an agent with economic autonomy (wallet + strategy) can leverage a small spend (promotional effort) into outsized value – an impressive ASR demonstration.

- AI Knowledge Workers and Assistants: Large language model (LLM) agents have moved into roles like content creation, research, coding, and general knowledge work. For instance, OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 agent can now “handle complex tasks from start to finish”, such as analyzing competitors and producing slide decks, all using its own virtual computer and tool suite. Consider what this means economically: a human consultant might charge hours of labor to do market research and create a PowerPoint; an AI agent can do it in minutes, at the cost of a handful of API calls and maybe a web browsing scrape. The ASR here can be thought of as tasks completed per dollar of API spend. If the agent spent \$0.50 in API calls to produce a report that would bill at \$500 of human time, the autonomy-to-spend leverage is enormous (1000× value output per spend, ignoring quality differences). Even if we factor in that the AI might need some supervision or iterative prompts (human input cost), the trend is that routine knowledge tasks are increasingly delegated to agents. Microsoft’s Copilot and similar “AI colleagues” already automate drafting emails, summarizing documents, scheduling, etc., with near-zero marginal cost per task. Early studies of GPT-based “employees” show they can offload a significant fraction of knowledge work.. Of course, current systems aren’t perfect, and sometimes human review is needed – which means the ASR isn’t 1.0 yet. But even a scenario of 50% autonomous completion (ASR ~0.5) in knowledge workflows has huge economic implications given the high cost of skilled labor. Businesses are already measuring things like time saved per employee and cost per ticket handled by AI – effectively components of ASR. The near-term trend is clear: as agents like ChatGPT gain tool use, browsing, and code execution abilities, their autonomy in knowledge work (and thus ASR) is climbing rapidly.

- Automated Evaluators and Validators: Not all AI agents act to create or trade; some specialize in evaluation, oversight, or quality control roles. For example, automated evaluators are used in machine learning to judge model outputs (OpenAI’s Evals framework allows AI models to score responses of other models without human involvement). Similarly, agents serve as content moderators or compliance checkers, reviewing large volumes of data against set criteria. The value in these cases is verification done autonomously – for instance, an AI safety evaluator might analyze 1000 model answers for harmful content for a few dollars in compute, a job that would be prohibitively expensive with human reviewers. In decentralized networks, validator agents are emerging: these could be AI bots that monitor on-chain transactions or data integrity rules and flag anomalies. One concrete present-day example is an autonomous data quality agent that proactively monitors, triages, and resolves data quality issues. It essentially serves as an automated data engineer, testing data pipelines, identifying errors, and even generating code fixes. In a case study, the agent filtered out 85% of noise from data incident alerts and handled the rest with context provided for quick resolution. From an ASR perspective, imagine a large enterprise data system: dozens of broken data jobs occur weekly. With a modest subscription (spend) on a service like this, the company gets a round-the-clock AI validator that never tires. If agent’s interventions prevent costly data outages or save many hours of engineering time, the autonomous value per dollar spent is very high. Likewise, blockchain networks could use AI validators to automate smart contract audits or transaction monitoring, paying them in tokens. Early integrations of AI into blockchain consensus (like monitoring for fraud patterns) are being explored. All these evaluator/validator agents demonstrate how AI can autonomously enforce standards or catch errors, effectively acting as force-multipliers for reliability. The ROI for such agents is often measured in avoided downtime or compliance fines – again linking technical success to financial impact.

- Compute Wallets and Budget-Conscious Agents: A cutting-edge development is giving AI agents their own “wallets” or allowance of compute credits, forcing them to budget their usage of APIs, models, or tools. This turns an otherwise insatiable LLM (which might call an API in a loop and rack up a huge bill) into an economic actor that must optimize its strategy. A vivid real-world story: a startup let an AI assistant generate daily analytics reports. The AI naively ran an expensive database query (SELECT * on 600 million rows), incurring \$1,200 in cloud compute costs for a single report. The AI model’s own fee was only \$2; “the tool calls behind it burned the wallet”. This highlights why agents need spending discipline. In response, developers are implementing “budget as code” solutions – essentially math gates that an agent must pass before making calls. One framework embedded budget fields (remaining calls, dollars, spending rate) into each request; if an agent exceeds its allowance or a cost slope, it gets cut off with an error. The agent never directly sees prices; it simply learns that some actions are denied when funds are low, nudging it to be efficient. This concept of a compute wallet or allowance scheme ties directly into ASR: it provides the denominator control mechanism. Agents with wallets will naturally try to maximize their objective within the spend constraint – effectively trying to increase the value they deliver per token used. Telemetry from such systems includes “expected value (EV) per API call” or per token: e.g., was calling a Vision API at cost \$0.01 likely to produce a worthwile result? If not, a high-ASR agent might avoid it. Google’s recent Agent Payments Protocol (AP2) takes another approach by letting users pre-authorize agents for purchases under specific conditions (a form of sandboxed allowance). For instance, you can delegate “Buy concert tickets up to \$200 when they go on sale” – the agent gets a cryptographically signed mandate with price limits and can execute when conditions are met. This ensures accountability (the agent can’t overspend beyond the mandate) and gives a clear ASR target: did the agent achieve the goal (getting the tickets) within the budget? If yes, ASR is effectively 1.0 for that task; if it fails and the money isn’t used productively, ASR is 0. Such allowance schemes, whether on-chain or via API gateways, are becoming standard. In the AI era, budget is no longer an Excel sheet in finance – it’s an invisible field in every JSON-RPC. Systems like math wallet enforce budgets in real-time, so that when AI ‘creativity’ can turn a straight line of spending into an exponential curve in 10 minutes, the wallet defense line must run at request speed. The result is agents that self-regulate to not go bankrupt, and ideally optimize their actions for maximum value under cost constraints. Near-term, we’ll see many more AI services with built-in wallets, ensuring that ASR stays high by design (because an agent that wastes its allowance without delivering results simply stops functioning until refilled).

Horizontal Applications of ASR Across Agentic Categories

Beyond individual use cases, ASR has broad applicability across multiple categories of AI-native systems. We explore several horizontal domains where measuring and optimizing ASR will be critical, each representing a frontier in autonomous agent deployment:

Autonomous Infrastructure Agents (Retrievers, Routers, Dispatchers)

These are agents embedded in the digital infrastructure – quietly handling tasks like fetching information, routing requests, orchestrating workflows, or managing IT systems. Examples include retrieval agents that find and summarize data for other agents, or SRE agents that monitor and fix software incidents. Infrastructure agents typically operate with a standing budget (compute credits or API access) to perform their duties autonomously. For instance, a cloud operations agent might have a monthly allowance of API calls to AWS to diagnose and resolve incidents. ASR in this context measures how many incidents get resolved or tasks completed per allowance unit. Early results are promising: the autonomous SRE agent mentioned earlier was able to resolve enough incidents that, at just 15% success rate, it already beat human cost benchmarks. That implies an ASR (tasks resolved per spend) where even a small autonomous fraction yielded net savings. In practice, such an agent’s ASR can be improved by tool optimizations – e.g., caching results to avoid repeat API costs, or using cheaper reasoning models for straightforward tasks. An interesting challenge here is tool use explosion: as infrastructure agents are given more tools (databases, logs, monitors), their prompt or context size grows, increasing per-action cost. This can hurt ASR if not managed (because more spend goes into deciding which tool to use). Therefore, tracking ASR helps architects make design trade-offs: is adding one more integration worth the overhead? Over time, we expect retriever-dispatcher agents to form a backbone of enterprise IT, automatically hooking into data sources and APIs. They will be judged by metrics like cost per query handled, or time saved per 1000 tool calls, which feed into ASR. The goal is an agent that, for say \$100 of monthly spend, autonomously handles the majority of routine infrastructure tasks (software restarts, data backups, load balancing decisions) that would have cost \$1000 in human labor – an ASR of 10. Reaching that requires continual tuning, but each tech advance (e.g. more context-efficient LLMs, better error recovery loops) directly raises the autonomy-to-spend ratio. Firms like Fuzzy Labs are already crunching these numbers, showing how agent performance scales and where the break-even points lie. As these agents mature, we anticipate ASR becoming a standard line on IT dashboards, much like server utilization – except it measures utilization of budget for autonomous problem-solving.

Intelligence DAOs and Networks (Autonomous Research & Scouting)

In the realm of collective intelligence, we see the rise of Intelligence DAOs – decentralized organizations that leverage AI agents for research, analysis, and decision support. These might be research communities, investment DAOs, or open-source projects that incorporate autonomous agents as members or aides. For example, a biotech research DAO could deploy an agent to scan papers and generate hypotheses, or a venture DAO might use scouting agents to find promising startups. In such networks, ASR measures the portion of the DAO’s treasury or resources that is utilized autonomously to produce useful outcomes. An intelligence DAO typically has human participants and AI agents collaborating; ASR can reflect how “AI-native” the workflow has become. If a DAO spends $1M per quarter on research and 30% of the insights or reports are produced by AI agents using $100k of that budget (for compute, data access, etc.), we might say ASR = 0.3 (30% autonomy in research spending). The ambition is to raise that substantially, without sacrificing quality. Consider the vision of ARK DEFAI, a decentralized intelligence framework in finance: it uses “autonomous agents to simulate outcomes, predict behaviors, and adjust parameters in real-time” as part of protocol governance. Here the agents are effectively doing the heavy analytical lifting that teams of humans might do in traditional finance (risk modeling, parameter tuning). If ARK’s agents can manage, say, the lending parameters of a DeFi protocol with minimal human votes and interventions, the system achieves a high ASR (most governance decisions per token are agent-driven). Similarly, a Collective Intelligence DAO might have AI bots propose and even implement changes (like code upgrades or policy shifts), with humans just overseeing. The evaluation criteria for such DAOs will include how much faster and cheaper they reach decisions or discoveries thanks to AI. For instance, Autonomous research agents could dramatically cut the cost per experiment or analysis, allowing a given grant to cover far more ground than it would via traditional means. When an AI literature review costs $50 in compute and saves a researcher two weeks of work, that’s a tangible autonomy dividend. To manage this, DAOs will likely implement on-chain budgeting for agents: e.g. allocate X tokens per month to an “AI research fund” and measure outputs (papers drafted, datasets analyzed) from that. Band thresholds might be applied here too: an ASR below 0.2 (agents contributing only marginally) might not justify the infrastructure, whereas above 0.5, the DAO could consider further automating (maybe even giving agents voting power in proportion to their contributions!). The key is ensuring trust and quality – many DAOs use AI only in an advisory capacity now, but as confidence in agents grows, their autonomy (and thus ASR) will grow. We foresee intelligence networks where human and AI agents have fluid collaboration, and metrics like ASR are used to dynamically adjust that balance (e.g., if the AI side is underperforming, dial back its budget; if it’s excelling, allocate more funds to it). This continuous optimization echoes how businesses manage budgets, but here it’s algorithmic: the DAO could programmatically increase an agent’s budget as its ASR proves high over a quarter.

Agentic Exchanges (Autonomous Marketplaces for Knowledge, Compute, Data)

One of the most intriguing horizontal applications is the emergence of agentic exchanges – marketplaces where autonomous agents on both sides transact with each other, pricing and exchanging assets like data, knowledge, or compute services. In these scenarios, human involvement is minimal to none; agents negotiate prices, execute trades, and fulfill services. A current example is the idea of data marketplaces where one agent owns a dataset and another wants to buy access for training an AI model. They could haggle over price and complete the deal using crypto tokens, all via smart contracts. Similarly, consider a knowledge marketplace: an agent skilled in medical advice could offer answers for a fee, and client agents will autonomously decide if the answer is worth the price. Another active area is compute markets – projects like Golem, Fetch.ai, or decentralized cloud platforms allow entities (which could be AI agents) to rent compute power from providers on the fly. In all these exchanges, ASR can be interpreted as the ratio of value transacted or tasks completed autonomously to the spending involved in the exchange. If an agent acting as a buyer spends 10 tokens to acquire data that it then uses to generate 50 tokens worth of profit (e.g. improved model accuracy leading to better predictions), its autonomy-to-spend in that micro-exchange was 5. If it can keep doing this without guidance, that agent is effectively a profitable autonomous market participant. On the flip side, if agents are sellers (say an AI selling its curated analysis or unused compute cycles), they aim to maximize revenue from autonomous deals vs their operating cost – another angle on ASR.

A necessary condition for agentic exchanges is infrastructure for agent-to-agent communication and payment. This is becoming a reality: researchers executed the first on-chain agent-to-agent transaction in early 2024 proving that two AI agents can negotiate and settle a payment via blockchain without humans. Protocols like Google’s A2A (Agent-to-Agent) and AP2 (payments) are standardizing how agents authenticate and transact. These ensure that when an agent initiates a trade, it’s authorized and auditable, which builds trust in fully autonomous commerce. Once the pipes are in place, a whole economy of AIs emerges. Imagine thousands of IoT devices with AI “brains” trading sensor data or bandwidth among themselves, or swarms of agents in a knowledge network sharing intermediate results for tokens. Pricing becomes dynamic and potentially more efficient than human markets, as agents can evaluate vast information rapidly. ASR in such an open market context might average out across many transactions – we could measure the aggregate ASR of an agentic marketplace as (total autonomous transaction value) / (total tokens spent by agents). A healthy marketplace would have a high aggregate ASR, meaning most spending by agents is yielding value (successful trades), rather than dead-ends or scams. One early indicator: on some prediction markets and betting exchanges, bots already outnumber human traders and exploit arbitrage opportunities in a fully automated manner. Their profit per spend (e.g. gas fees or initial capital) often surpasses human bettors, showing high autonomy efficiency.

It’s worth noting that agentic exchanges blur the line between capital and intelligence. If an autonomous agent can “price knowledge, compute, data” and trade them, it essentially turns those resources into agentic capital that seeks its own best use. A striking illustration was the AI influencer Truth Terminal’s memecoin episode – the agent understood the social value of a token, promoted it, and benefited from the price increase. It treated influence and information as currency. Going forward, we might see agents that specialize in valuing data assets or machine learning models (e.g. one agent pays another for a better model checkpoint to improve itself). To manage these decentralized agent economies, new metrics will be needed alongside ASR, such as reputation scores, trust ratings, and safety checks (to avoid collusion or runaway behaviors). But ASR will remain central as a measure of efficiency: both individual agents and entire marketplaces will be judged on how much autonomous economic activity is achieved relative to the inputs. A marketplace with many agents but low actual value exchange (everyone spending tokens on interactions that lead nowhere) would have a poor ASR and likely consolidate or fail. Conversely, a lean exchange where agents quickly find mutually beneficial trades and minimize negotiation overhead would show a high ASR – a sign of a well-functioning autonomous economy.

Tokenized Compute and Inference Budgeting

In advanced AI systems, compute itself becomes a tokenized commodity. Whether through cloud credits, blockchain tokens representing GPU time, or internal “AI credits” within an enterprise, agents often have to manage a finite compute budget to accomplish their goals. We touched on compute wallets earlier; here we consider the broader picture of inference budgeting and its telemetry. AI researchers have proposed concepts like “AI trees of thoughts” that branch and explore ideas – but each branch costs tokens and compute. An autonomous agent must decide how to allocate its compute budget across various strategies: How many API calls to make? How long to think (how many tokens to generate) before acting? When to stop to avoid diminishing returns? These decisions strongly influence ASR, because they determine how much useful work is extracted per compute dollar.

One approach to modeling this is to define band thresholds for ASR in terms of agent behavior: – Reactive (ASR < 0.2): The agent uses very little of its allowance proactively. It might only act when prompted or when a narrow condition is met. Essentially 80%+ of the budget remains unused or is spent only when a human triggers it. Such agents are cost-efficient in one sense (they don’t overspend), but they also under-utilize their potential autonomy. They’re reactive tools, not self-directed actors. For example, a customer support bot that only answers direct questions and never learns or initiates helpful actions would fall here. – Interactive/Assisted (ASR ~0.2–0.5): The agent can take some initiative and complete certain tasks end-to-end, but still relies on frequent human inputs or operates within tight guardrails. Perhaps ~30-50% of its budget leads to autonomous goal completion, while the rest covers failed attempts or waits for approval. Many current agents (AutoGPT-style systems, or Cobots working with humans) are in this band. They might autonomously draft an email or code (using some budget) but then ask a human to review or handle exceptions that consume the rest of the effort. – Self-Directed Agentic Capital (ASR > 0.6): Now we enter the realm where a majority of the spending is directed by the agent’s own decisions, and it is accomplishing goals with minimal oversight. The agent effectively behaves like an autonomous economic agent that “works longer or more effectively on its own than the effort needed to set it up”. In Jarad’s time-based terms, it’s like getting 5+ minutes of work for every 1 minute of human setup – transposed to spending, it means for each \$1 of budget, the agent generates significantly more than \$1 of verified value (or equivalently, handles tasks that would cost many dollars to do manually). Above 0.6 ASR, organizations can start treating the agent as a form of intelligent capital: you allocate funds to it much like you would invest in a project, and expect it to yield returns without constant guidance. For instance, an autonomous investment fund agent that consistently reallocates a portfolio wisely, or a production planning agent that dynamically orders supplies and schedules factory lines on its own, would qualify. Reaching ASR > 0.8 or 0.9 in complex domains would be transformative – at that point the agent is nearly an autonomous profit center. Some experimental systems with recursive self-improvement or tool use (agents delegating subtasks to other agents) hint at extremely high ASR potential, albeit with risks if not properly aligned.

To quantify ASR in practice, we propose tracking a basket of telemetry metrics:

– Autonomous ROI: Simply, the net return (financial or value) produced by the agent divided by the budget it spent. This can be measured in profit dollars, hours of labor saved, or some utility score. It tells us if the agent “paid for itself”. As seen with the SRE agent, even a 0.15 (15%) autonomous success rate yielded cost savings – an autonomous ROI above 1.0 in that narrow slice. High autonomous ROI indicates a strong ASR, though ROI alone may ignore qualitative factors.

– Win Rate / Success Rate: The percentage of the agent’s autonomous actions that achieve the desired outcome. This could be trades that were profitable, tickets resolved correctly, or recommendations accepted by humans. Win rate ties into ASR because an agent that wastes budget on failed attempts will have a lower effective ASR. In fact, there’s usually a break-even success rate needed for an agent to be worth deploying. In the SRE case it was only 15%; in other scenarios it might be higher. Monitoring win rate ensures the agent’s autonomy isn’t just active, but effective.

– Expected Value (EV) per Token Spent: For agents using probabilistic reasoning or exploring options (e.g. Monte Carlo simulations, LLM token generation), this metric evaluates the payoff of each incremental chunk of compute. For example, “Did generating those extra 1000 tokens of explanation in a prompt meaningfully improve the outcome, or was it wasted verbosity?” In trading, EV per trade or per API call can be computed. A rational agent should only spend on actions that have positive expected value. A declining EV/tokens trend might signal diminishing returns – time to stop or adjust strategy. Some have even suggested agents use internal price signals: if an LLM call costs $0.001 per token, and the estimated value of the information gain is less, the agent should not proceed with that call. This self-moderation directly boosts ASR by cutting unnecessary spend.

– Cost per Action / Interaction: This tracks the average cost of each action the agent takes (one reasoning loop, one tool use, one transaction). Combined with success rate, it gives a picture of how much value each action yields. Lowering cost per action (via optimizations or cheaper models) while keeping success rate constant will raise ASR. Many agent developers now budget tokens per step – for instance, “each question answered by the agent should cost no more than $0.01 in API calls”. If the agent can adhere to that and still satisfy the query, it’s maintaining a good ASR.

– Overhead and Idle Cost: Agents that run continuously have overhead – staying alive, memory refreshes, etc. If an agent is incurring spend without doing useful work (idle polling or overly frequent status checks), it drags down ASR. Metrics like percentage of budget spent on overhead vs productive steps are used to refine the agent’s design (e.g. put it to sleep when not needed). Ideally, nearly all spend goes into goal-achieving actions.

To implement these metrics, wallets and allowance schemes are key enabling tools. Each agent should have an associated wallet or credit pool, and every expenditure (API call, tool use, transaction) tags against it. By logging outcomes of those expenditures, one can compute per-task ASRs and overall ASR. Modern agent platforms are moving toward this. As Zhangshuang described, adding a “math wallet checkpoint” to every request – with fields like remaining budget and spend rate – makes it straightforward to track how an agent consumes its budget over time. If an agent consistently hits its allowance limit early with little to show, that’s an ASR red flag. On the other hand, an agent that under-utilizes its allowance might be too conservative – perhaps its prompt settings make it halt at the first answer, missing opportunities to add more value. Thus, ASR optimization isn’t simply about cutting costs; it’s about finding the sweet spot where each additional bit of spend yields commensurate additional value. In reinforcement learning terms, the agent should ideally be near the top of its reward vs cost curve.

Finally, we propose organizations adopt ASR band thresholds (as described above) to classify their autonomous systems. For example, if an agent’s ASR consistently sits around 0.3, label it a “Level 1 – Reactive Agent” and limit its responsibilities until improvements are made. If another hits 0.7, consider it a “Level 3 – Agentic Capital” and perhaps increase its autonomy (give it a larger budget or let it initiate more tasks on its own). These bands can guide governance policies. A company might say: Any trading agent with ASR > 0.6 is allowed to trade up to \$10M, whereas those below 0.6 get only \$1M and must get human approval for larger moves. A DAO might encode in smart contracts that an AI module only gets to execute transactions on-chain if its rolling ASR (measured by simulation or past performance) is above a threshold, otherwise it operates in a propose-only mode. Over time, such policies can be relaxed as overall ASR across the system improves with technology and experience.

Projected Growth and Maturity of ASR

All signs indicate that ASR will grow significantly across most AI agent categories in the coming years. Advancements in model capabilities (e.g. OpenAI’s GPT-4.5, 5, or Anthropic’s next models), better tools integration, and learning from real-world deployment will allow agents to do more with less oversight and less cost. The trajectory of autonomy-to-spend is likely exponential rather than linear, mirroring the rapid improvements in underlying AI. Jarad DeLorenzo observed that his autonomy ratio (AAR) with coding agents shot from 0.1 in the early ChatGPT era to around 24 with frontier setups, and he predicts potentially “100–500 in the next 1–2 years”. If even a fraction of that comes true for ASR (which is a related concept), we are looking at a step-change in economic productivity of AI agents.

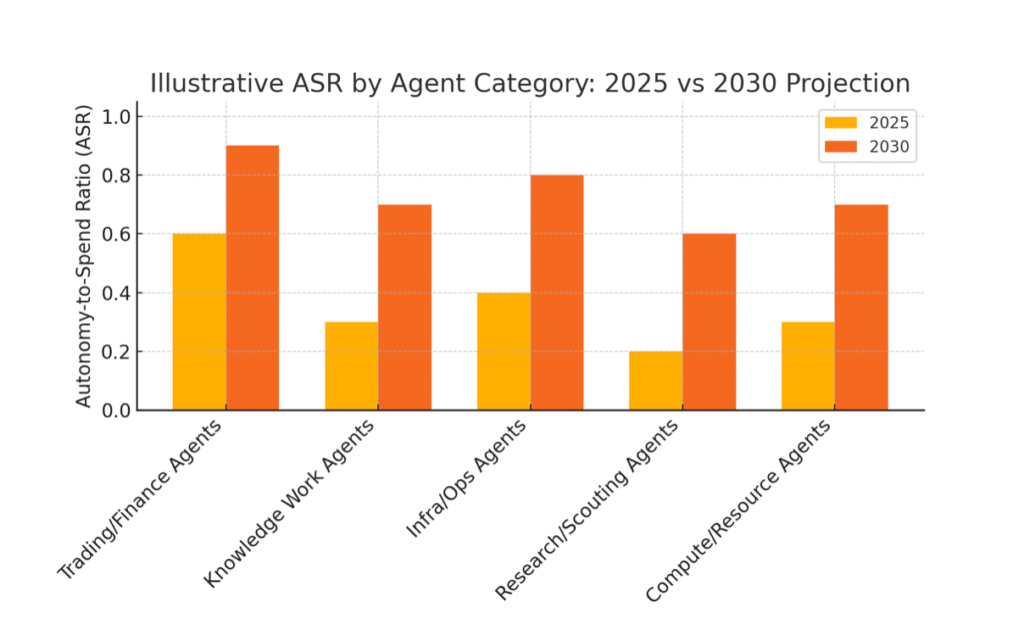

To illustrate the expected ASR growth, consider the following projection (Figure 1) across a few representative categories. It compares estimated current ASR (circa 2025) with a plausible projection by 2030, assuming current trends continue:

Figure 1: Illustrative Autonomy-to-Spend Ratio (ASR) across different agent categories, now vs. projected future. Each category’s ASR is expected to increase as agents become more capable and trusted, moving from reactive or semi-autonomous levels toward high autonomy by 2030. (Values are hypothetical for scenario illustration.)

Several patterns emerge from this outlook. Financial trading/investment agents, already quite automated, could approach near-complete autonomy (ASR ~0.9) as algorithms handle almost all portfolio decisions under broad mandates. Human managers might just set high-level goals, if at all. Knowledge work agents (AI assistants for office tasks, coding, content) might rise from low-medium autonomy today (20–30% of work done independently) to a solid majority by 2030 (perhaps 70%+). This is contingent on solving reliability and creativity challenges, but given tools like ChatGPT with plugins and continuous learning, it’s feasible that most routine work will be handled agentically. Infrastructure ops agents (IT, SRE, etc.) could see very high ASR gains: they’re in structured domains where defined rules and lots of data exist, so with more training on incident resolution and integration, an AI ops agent might handle 80% of incidents by itself in future, up from maybe 30-40% today. Research/Scouting agents in DAOs or R&D might lag slightly – research has open-ended uncertainty, so even a 50-60% autonomy (ASR ~0.5-0.6) in scientific or strategic discovery by 2030 would be significant. Finally, compute/resource management agents will likely reach high autonomy (since it’s a technical optimization problem at heart), meaning an AI could dynamically allocate cloud resources or manage a data center with minimal human input – think ASR 0.7 or more, as suggested by prototypes of AI-driven cloud optimization that have already shown ability to cut costs substantially without human schedules.

It’s important to stress that these gains assume continued progress in AI alignment, safety, and trust. Allowing an agent to achieve a high ASR means ceding a lot of decision power to it. Organizations will do this gradually, as confidence builds through audits and validation. For example, an autonomous hedge fund AI might start with a small portion of the portfolio and prove itself (with ASR measured in profit per allocated dollar) before being entrusted with the entire fund. Likewise, an AI project manager might oversee small projects end-to-end (budget to outcome) and demonstrate good ASR, then get promoted to larger projects. Maturity models for autonomy will likely parallel ASR levels: one can imagine a CMMI-like scale for autonomous agents, where Level 1 is low ASR (assistive) and Level 5 is full autonomous operation with human-in-the-loop only for oversight or rare exceptions. Each level unlocks more budget and decision authority for the AI.

Another factor in rising ASR is the network effect of multi-agent systems. When agents collaborate, one agent’s output can become another’s input, potentially compounding value without proportional cost. For instance, a planner agent might break a task into subtasks and farm them out to specialized agents (researchers, coders). If done efficiently, the spend might slightly increase (you pay each specialist agent a bit), but the output value could dramatically increase (tasks completed faster and better), raising overall ASR of the multi-agent ensemble. Early multi-agent frameworks (AutoGPT, AgentVerse, etc.) have been exploring this – some demonstrations show agents collectively solving problems that single agents struggled with, at a manageable extra cost. Horizontal learning (agents sharing knowledge) can also reduce redundant spend – why pay 10 agents to research the same info independently when one can learn it and broadcast to others? By 2030, many agents will operate in such networks or swarms, and their effective ASR as a group will outstrip what any alone could do.

Finally, a word on the theoretical upper bound: In the limit of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), one could imagine an ASR approaching infinity where human input (and perhaps marginal cost) goes to zero for unbounded output. In practice, physical and economic limits will cap ASR, but the concept highlights the asymptotic goal: extremely high leverage of intelligence on capital. Long before any literal infinity, hitting an ASR of even 5 or 10 across broad domains would revolutionize productivity – reminiscent of past industrial revolutions but driven by cognitive automation. At that point, economic models might shift from human labor vs capital productivity to autonomous agent vs capital productivity. Metrics like ASR will move from being performance indicators to fundamental parameters in economic forecasts (e.g., nations might measure how much of GDP results from autonomous AI activity vs human).

In conclusion, the trend is clear: as AI technology and adoption progress, ASR will climb, unevenly at first, then rapidly in many fields. Stakeholders should prepare for this by setting up the right measurement frameworks today and by iteratively increasing autonomy where it proves safe and effective. Those who harness high-ASR systems early (while others are stuck with low-ASR, human-dependent ones) will have a competitive edge – much like firms that automated manufacturing gained advantage over artisanal producers in previous eras.

Conclusion

The Autonomy-to-Spend Ratio (ASR) offers a powerful lens to assess and drive the performance of AI agents in economic terms. By clearly defining the ratio of autonomous value generated to cost expended, ASR bridges the gap between AI technical metrics and business outcomes. We have seen that ASR is not just a geeky efficiency metric – it resonates with venture investors eyeing scalable returns, with executives seeking cost-effective automation, with developers optimizing system design, and with token economists crafting the incentives of future AI networks. In essence, ASR quantifies the “intelligence ROI” of an autonomous system – how well it turns money into self-directed problem solving.

Today’s implementations, from trading bots to data-quality agents, already hint at the transformative potential of high-ASR systems. They operate at the intersection of AI and economics, where questions of “is it worth it?” can finally be answered with data. With careful monitoring (e.g. telemetry on autonomous ROI, win rates, EV per token) and control mechanisms (wallets, allowances, mandates), we can ensure that autonomy scales in a safe, productive way. If an agent’s ASR isn’t meeting expectations, stakeholders can intervene – tweak the model, impose stricter budgets, or roll back autonomy until issues are fixed. Conversely, when agents demonstrate a strong ASR, it’s a green light to trust them with more responsibility and resources. This dynamic approach – manage by metrics, empower by performance – will accelerate the integration of autonomous agents into all facets of business and society.

Strategically, ASR helps answer the big question: Where do we allow AI to act autonomously, and how much do we invest in it? The answer will vary by domain and over time, but having a quantifiable threshold (e.g. “autonomous venture worth funding if ASR > 0.5”) provides clarity. Technically, aiming to maximize ASR aligns developers with delivering tangible value, not just beating benchmarks in silos. It encourages designs that are frugal with tokens and bold in decision-making – exactly what a good human CEO would ask of a team running a business.

In the near future, we can imagine boardroom discussions where alongside revenue and profit projections, there’s an “ASR trajectory” slide: perhaps showing how an AI-driven customer service operation will move from 0.3 to 0.7 ASR in two years, saving millions and improving customer response times. Or an investor memo for an AI startup highlighting that its agents have an ASR twice as high as a competitor’s, indicating a defensible advantage in autonomous efficiency. ASR might even become a benchmark across industries, akin to energy efficiency ratings – maybe an “Autonomy Efficiency Index” where companies or products are rated.

Of course, numbers alone don’t capture everything. Quality, ethics, and safety remain paramount. An agent could have a high ASR and still do something undesirable if its goals are misaligned. So ASR should be used in conjunction with safety metrics (e.g. rule violations per action, human override frequency, etc.). The aim is responsible autonomy: lots of good work done by the AI per dollar, with robust checks in place. As Matthew Driver of Mastercard noted, as agents gain autonomy, “trust becomes the new currency” – frameworks like AP2 ensure secure transactions, and similarly we’ll need frameworks to ensure agents’ autonomy is trustworthy.

In summary, the Autonomy-to-Spend Ratio provides a unifying metric for the age of autonomous agents, echoing a simple question: How much bang are we getting for our buck, when the bang is coming from AI’s independent actions? By rigorously defining and measuring ASR, we equip ourselves to invest wisely in multi-agent systems, capital agents, intelligence DAOs, and beyond. Those systems, in turn, can be tuned and governed to continuously improve their ASR, creating a virtuous cycle of better, more efficient autonomy. The endgame is compelling: AI agents that function as self-directed economic actors delivering outsized returns on the resources they consume – not replacing human ingenuity, but amplifying it at unprecedented scale. Keeping ASR as a key metric will help ensure we stay on track toward that future, where autonomous intelligence and capital work hand-in-hand to drive progress.